| |

|

The volcano and its peaks

hidden by clouds |

From Bali to Komodo Is., the sea plunges among many isles and small islands. Among these,

one entered my heart for its beauty: Sangeang Is.

Its thin and black volcanic sandy bottom is so fine, passing through everything, that one

is compelled to clean and polish each o-ring after every dive. It is a paradise for nudibranchs of

many different species, meeting them either in the sloping black sandy bottom or over the small south wall;

this is a precarious agglomerate made of sand, stones and coral, slowly splitting and rolling down under

the pressure of new sand and soil, continuously swept into the sea by the still-active volcano.

The wall rises over a bottom between 60 and 75 feet deep; at that point the sandy slope rises,

broken by small coral blocks. Varicolored crinoids are everywhere, standing out from the black wall, among

alcyonarians, corals and sponges. Each hole and crevice is a den for fishes.

At the edges of the wall, the corals, beaten by currents over its top, form an infinite-colored garden.

Unfortunately, a part of the wall is collapsed. The pressure of the water moved by a vigorous flipper is enough

to create a small landslide with the consequent fall of stones and corals on the bottom accompanied by a cloud

of black dust.

Last year, here was the den of a small frogfish, white with red spots. Now, every trace is lost of that

beautiful and rare specimen.

| |

|

| Sangeang view in the afternoon |

Sangeang is a volcano with two craters reaching 6500 feet and separated by a deep verdant valley.

I remember the first time I saw this island: I was awakened at dawn, after a night of navigating, by the

perfume of croissants just out of the oven. Dense low clouds hid its tops; looking through the haze of the

valley between the two tops, I thought, if King Kong were real, he should choose his home here, in this valley

deep and hidden in the shade of the two high craters.

Only in late morning, when the sun manages to dispel the dense clouds, does Sangeang appear in all

its beauty, with its shades of color, the high tops of its craters, its ridges and canyons sloping to the sea.

Some palms and other trees add a lot of green to wavy hills stretching at the base of the volcano. Along the southwest

side it is possible to observe some pastures for livestock and small lands cultivated by the roughly 100 inhabitants

of the primitive village, their pirogues lined up along the short beach.

Going ashore, a few persons came towards us, almost all wrapped in their sarongs. Most part are

seniors, women and children. Some dog barks, chickens continue to peck among stones and dust. The huts are

wooden, lifted by short stilts. The thatched roofs are sloping and protect from the rain and sun.

A women works on a deep wood mortar with a long pestle, a child is wrapped in her sarong. It is a

typical scene, common worldwide. You can see it in all the African and Asiatic villages: the same mortar, the

same pestle, the same incessant movement infinitely repeated.

The people welcome us, smiling. The children open their eyes, I don't know whether made curious or frightened.

Visitors are not frequent on this small island.

I notice the lack of men, probably they are working: some tend the livestock, cows and goats,

but most are at sea, in small dugout pirogues with a bamboo outrigger to ensure stability. Almost all the

pirogues have a short mast where colorful triangular sails are hoisted. They start at dawn and come back

at sunset with their loot: a few fish captured with simple fishing rods. Others go to Sumbawa Is., a few tens

of miles away, for trade and business.

On their return, when the wind is not favorable, they go ashore where possible, and continue by foot among

rocks and stones, dragging their pirogue against the wind by a long line.

| |

|

| Woman with a typical mortar |

Leaving Sangeang, I ask to confirm if we'll cross again at our return towards Bali.

«Certainly» I'm answered, «and take a very particular night dive...»

«That is?» I asked, curious.

«It is a new experience, we never tried before. This idea came from watching a documentary on the BBC.

This is the idea: we stop adrift along the northern side of the island, where the bottom deepens to about

6500 feet. We let out some sea some lines of about 65 feet with some lights, and there we hang, waiting

to observe the night ascent of strange creatures from the abysses»

The idea was curious and fascinating, perhaps my occasion to take some really "unique" photos. At the time

I did not weigh the matter completely; we should consider it after some days, on our way back, if sea and

wind allow this experiment.

The days went by in a hurry, and here we are back in Sangean.

It is dark when the ship turns off its engines and stops powering among the waves. The current is apparently

weak. The ship is slowly adrift, driven by a light wind.

The moon has still not risen and the darkness is everywhere.

Some hands see to the lowering of four lines with a heavy lead and some strong small lights at the end,

two lines amidships and the other two at the prow, a distance of about 33-40 feet. This should guarantee

visibility among the many members of the dive.

We begin slipping on our wetsuits and preparing. The plan is to have two divers for each line, for a maximum

time of 30 minutes to give enough time for everybody of try this dive.

And now you'll hear the best of it... Sure, wanting to do something is one thing, but

it's another thing slipping on the wetsuit, knowing that in few minutes you'll be hanging in "nothing"...

One of the divers, the editor of many underwater books (do you remember those three spring-bound books on the

Caribbean?) gets the idea to tell that once, I don't remember in which Pacific area, he was captured by a

giant squid and fought bravely tied to a line, till the squid let go its hold.

Just the right moment for this kind of story!

Finally we are ready. My companion and I decide to swim to our line at the prow, and only to dive there.

I enter the water and begin to swim along the ship to the prow. I turn and don't see my companion; small waves

hide him from my view. I look high, I search for his wife; perhaps she sees him from above. No, she doesn't see him,

either. I look low and see he is already diving and swimming to the line. I, too, dive and reach the line.

We go down to 65 feet and there we stop to look around...

We are practically surrounded by a cloud of plankton. The visibility is reduced, it is hardly

possible to see the lights from the other lines, like ghostly green glares throwing light cones that melt into

the dense suspension.

It is immediately clear that it is very difficult to take photos in these conditions. It is only possible to

observe the multitude of small organisms surrounding us, and to try to look around in the darkness, through

the "fog" of plankton.

My companion, without saying anything, begins to go up along the line.

«Perhaps he is checking the visibility at surface,» I think, and I start observing again: larvae,

small worms. I'm surrounded by whitish and fluorescent microorganisms of every possible shape, like small

snowflakes, each different from the other.

I try to observe through the lens, but the autofocus cannot work in these conditions. Everything is moving,

myself included, driven by a light current.

It's better to forget the camera and to enjoy that strange sensation of being suspended over the abyss.

Some minutes go by; I look up and no longer see my companion. No lights upon me, I can't quite

see the large hull of the ship, too little visibility.

Now a doubt rises within me: my situation is so paradoxical, to think for a moment that this could be a joke.

Effectively, the light of my line is much deeper than the expected 65 feet.

«Perhaps are we over a sandy bottom at 90 feet? Perhaps is this a well organized joke?»

I go down along the line to the bottom; reaching the end of the line at 105 feet, I look down. No sandy

bottom is visible, only total darkness and the cloud of plankton.

| |

|

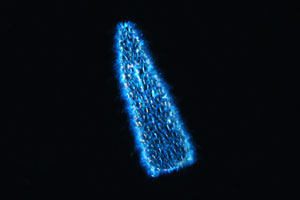

Pyrosome - the only photo I shot,

pelagic colonial tunicate

Pyrosoma sp. |

I return again to 65 feet and there I stop. Now I am accustomed to this situation, the early

unease has gone away.

The line gives me reassurance; I detach only for short moments to better observe some larger organisms passing

at a few feet. Then there are the slight greenish dazzles of other lights, evidence that others are in the

same position, that I'm not alone.

I look around 360° and feel a strange sensation, absolutely new.

It is not the usual sensation of being underwater at night. The absence of weight, the darkness, and the lack of

landmarks causes me to imagine myself as an astronaut surrounded by the Milky Way. The line is my umbilical cord

to the space shuttle, around me the infinite, dark and mysterious.

Yes, because it is unimportant if under you are 300, 3.000, 30.000 feet or the infinite.

You have no landmarks.

It is difficult to "locate" yourself mentally in three dimensions under these conditions. There is only the

darkness, the nothingness (or everything?)

You know that the light of your torch allows you to rove in only an infinitesimal part of what surrounds you,

that your vision is partial, distorted, and restricted. Under and around you is a vast world, and vision and

knowledge are precluded.

Yes, I felt more like an astronaut inside a lost galaxy than a diver surrounded by the lukewarm Indonesian waters.

I am lost in my thoughts, wrapped in the cloud of plankton, witness to how much this sea is

imbued with life, now observed for the first time from another point of view. Life abounds everywhere, even in

that endless darkness, in a lost point of the ocean. But how much life does this sea contain? The mind loses

itself before these dimensions, much too great to be quantified and rationalized.

| |

|

Sangeang view, at sunset,

from Banta Island |

I look at the dive computer. Only fifteen minutes have gone by; nevertheless my trip in the

Milky Way, in the infinite spaces, seems to me to last hours.

I make another quick check of the situation. I have by now lost track of my companion. I see some moving

lights from the other side of the hull. I decide to see what the others are doing, if they have seen some

strange creature, something of interest.

I let go the line, my umbilical cord, and swim quickly to the light on the nearest line,

never looking away from my computer to maintain the same depth.

But there is nobody. The light on the line, moved by the current, confused me, I believed it was someone

else's torch. I see another light and swim to it. The same story, a line with nobody, its small light waving

with the current.

The only thing to do is to go to the fourth line, on the same side of the hull where I started.

I find no one there, either. Everyone has disappeared.

I check the computer: twenty minutes have gone by. I still have ten minutes at my disposal, but now the

consciousness of being alone leaves me uncomfortable.

It is strange how one's mind clings to things to acquire confidence. The presence of someone 30 feet away,

unable to see you, makes no difference if something really great arrives from the abyss.

But now I ask to myself where the others are, why is nobody in the water except me?

And if did something happen, an unexpected event I did not realize?

I decide to go. A spell is broken. It is time to come back to the surface.

Everyone is on board, some already dry and dressed.

«I got out because I was cold, hungry, there was too much suspension for photos»,

these were the excuses.

It seems everyone has returned from a banal day out in the country...

Again, I experienced how people are averse to expressing their own emotions.

And how everyone has different reactions to particular experiences, sometimes too personal and internal

to express in mere words.

I tried, by the story of this night dive.

|